In Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, scientists at the National Public Health Institute examine cloudy water collected from city drains. These samples hold valuable information for public health.

For Professor Isidore Bonkoungou, a bacteriology and virology specialist, this careful work marks the start of a significant change. “We are still in the early stages,” he said, “but wastewater surveillance gives us a chance to detect diseases before they spread. It helps us understand what is happening in our communities even before the first person goes to the hospital.”

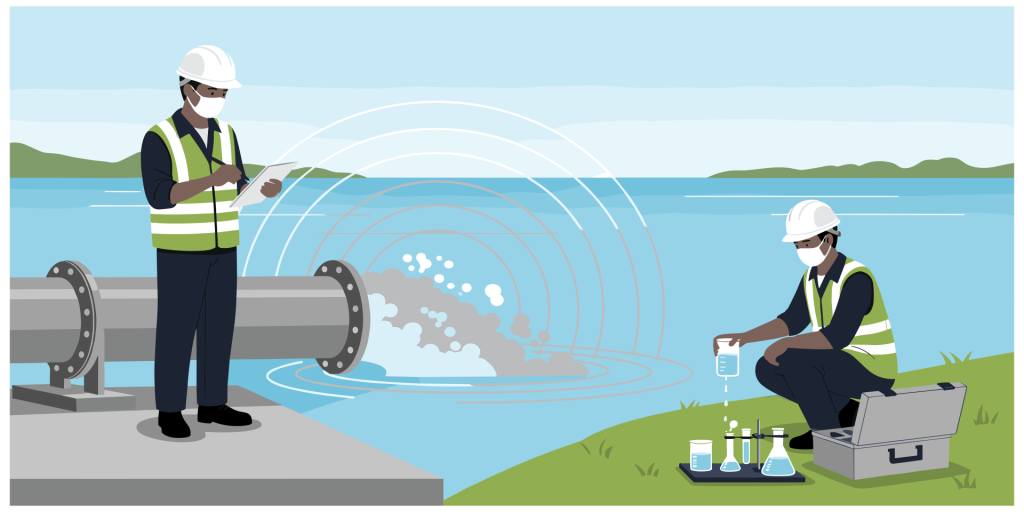

In many African countries, Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance (WES), which involves regularly collecting and testing samples from sewage and surface water, is emerging as a crucial early-warning tool. By detecting disease trends days or weeks before people develop symptoms, WES helps countries respond quickly to outbreaks such as cholera, polio, COVID-19, and antimicrobial resistance. Used alongside other surveillance approaches, WES strengthens public health response.

Burkina Faso first adopted wastewater environmental surveillance to monitor polio. Teams collect weekly samples in Ouagadougou and send them to Dakar for testing. Professor Bonkoungou’s laboratory at the University Joseph Ki-Zerbo has since expanded its work to include surveillance for antimicrobial resistance (AMR), tracking how bacteria adapt to resist antibiotics. “We report our environmental data every trimester to the Ministry of Health,” he explained. “The Ministry then combines it with clinical data to report to global systems such as the Global Antimicrobial Resistance and Use Surveillance System (GLASS). This helps create a One Health picture of resistance patterns.”

This expertise proved decisive during a recent hepatitis A outbreak. “We were able to show that contamination came from traditional wells people used for drinking. That insight guided the Ministry of Health to act quickly,” he recalled. “Now, we want to move from responding to predicting.”

Building on these advances, Burkina Faso has received support from the Pandemic Fund to create its first national wastewater surveillance plan. “We started drafting it in August,” Professor Bonkoungou said. “The plan brings together all ministries — environment, animal health, human health and local government. The goal is to build a national system that matches our country’s needs.”

That spirit of collaboration was at the forefront of the Africa CDC Continental Workshop on Wastewater and Environmental Surveillance, held in Nairobi recently. Over 50 delegates from AU Member States, WHO, the International Livestock Research Institute, the United Nations Environment Programme, the Gates Foundation, the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC), Health Emergency Preparedness and Response (HERA), and the Pasteur Network gathered to chart a unified strategy for integrating WES into national systems.

Opening the meeting, Dr Merawi Aragaw, Head of Surveillance and Disease Intelligence at Africa CDC, called for coordination and sustainability: “We want to optimise surveillance mechanisms on the continent, leverage the existing environment to generate more intelligence, and consolidate strategic guidance for all Member States. We must avoid working in silos and instead build a sustainable system where countries support one another with coordinated, data-driven solutions.”

The meeting explored how WES complements the Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response (IDSR) framework, supports One Health approaches, and offers a population-wide lens for decision-making. “Countries need predictable financing to sustain pilot programmes and scale up what works,” said Dr Supriya Saha of the Gates Foundation on the importance of coordinated funding. Dr Anastacia Keller of ECDC HERA shared lessons from Europe: “Through our partnership with Africa CDC, we can help strengthen capacity for multi-pathogen monitoring and contribute to a global network.”

Over three days, delegates assessed Africa’s WES landscape and drafted the first Continental WES Strategy, focusing on transforming pilot efforts into sustainable systems. The strategy outlines a roadmap that includes validation by November 2025, the establishment of a Continental WES Consortium and annual conference, and the creation of a hub-and-spoke network linking national and regional laboratories. It also calls for strengthening the Community of Practice for knowledge exchange and collaboration, and for identifying financing and governance mechanisms to ensure sustainability. The official launch is planned for March 2026, marking a milestone in integrating WES into public health decision-making.

Professor Bonkoungou sees Africa CDC’s work on Wastewater Environmental Surveillance as a timely reinforcement. “This meeting showed us that the challenges we face are common across Africa. By collaborating, we find answers. We will adapt the Continental WES Strategy to our own, and we hope Burkina Faso will be among the first countries to pilot it.”

Establishing or expanding WES programmes requires a clear implementation framework that defines resources, infrastructure and country-specific steps. For sustainability, countries should integrate WES into health strategies and secure reliable funding. Building skilled personnel and laboratory capacity, especially in resource-limited settings, relies on targeted training, technical support and partnerships.

Integrating WES data with existing surveillance systems through standardised reporting will enable timely, actionable responses and maximise the impact of WES initiatives. By harnessing wastewater environmental data, Africa’s public health experts are building the continent’s first line of defence against future epidemics. As WES expands, Africa’s scientists and public health professionals are working together to transform environmental data into early action — strengthening the continent’s resilience against emerging threats.