In March 2022, the Kenyan Ministry of Health lifted all COVID-19 restrictions, including wearing of masks, restrictions on large crowd gatherings, and quarantine measures for confirmed COVID-19 cases. This move not only reduced the risk perception of COVID-19 among citizens but also saw related mass media messaging drastically reduced, especially on mainstream media platforms, which were the leading platforms used by the Kenyan Government to communicate key information on COVID-19. Both outcomes negatively impacted COVID-19 vaccination uptake by the eligible population. The Saving Lives and Livelihoods (SLL) programme by Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) in partnership with Mastercard Foundation, was initiated in July 2022 to support the Kenyan Ministry of Health to ensure that 70% of the eligible population in the country is vaccinated against COVID-19 to build immunity and create resilience. The COVID-19 uptake in Kajiado county as of December 2022 was at 40.1% which was below the national target of 70% of eligible population. One of the bottlenecks to achieving this target was the low risk perception of the pandemic, which meant that the project would have to develop new strategies to increase the coverage and uptake of the COVID-19 vaccine.

Ann Mwangi, aa attending nurse at the Government of Kenya (GK) Prison Dispensary, Kitengela observed the challenge in COVID-19 vaccination uptake at the facility and initiated an innovative approach to increase vaccine uptake. According to her, “it is rare to find people walking into a facility to get vaccinated voluntarily. People mostly go to the facility when requested to get the vaccination certificates for work, or those seeking to travel outside the country.” Ann further explained that the community’s low health-seeking behaviour (especially surrounding COVID-19 vaccination) is what necessitated them to move from their facilities to start reaching out to the communities directly. Ann indicated that in the past, they would conduct outreaches using public address systems to mobilise people to get vaccinated, but this approach proved ineffective as it failed to facilitate interaction between community members and volunteers. The PA systems did not provide opportunities for communities to ask questions and for the volunteers to dispel the misinformation regarding the COVID-19 vaccine.

Simon Mwangi, a Clinical Officer at Gataka Health Center and the lead of one of the COVID vaccination teams, added that when messages are shared in large groups, mob mentality is likely to occur, which may cause people to resist taking the vaccine because they want to act as a group. Based on these shortcomings, the idea of a door-to-door vaccination approach was borne with improved interpersonal engagements with communities in high-traffic areas.

The outreach teams found the door-to-door strategy effective for accessing Chanjoke, which is the national reporting system for COVID-19 vaccinations, and following up on individuals’ vaccination status, including booster doses. For this approach, the facility follows a monthly household visits plan derived from facility vaccination micro plans. The community health promoter shares planned visits with the facility nurse who then gives a go-ahead for the health teams to visit the households. The health workers in the team ensure that enough vaccines, drugs and other commodities necessary for the integrated door-to-door visits are available. During the door-to-door service delivery, household health talk is also carried out to identify other health gaps in the household. All health gaps identified services are offered immediately and where necessary, referrals are done to the health facility. This close interaction with people highlighted a prevalent lack of knowledge about booster shots, enabling the teams to educate communities about vaccine types and the importance of full immunization.

“Our one-on-one interactions with the community led to more personalised follow-ups, significantly increasing the number of people vaccinated. Some people claimed they were fully vaccinated, but our system checks often revealed incomplete vaccination schedules. We would then clarify and guide them on the remaining necessary doses, Ann narrated.”

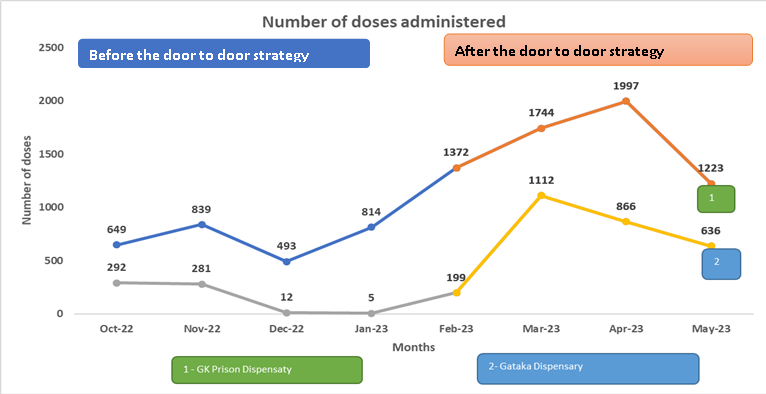

The graph below illustrates the impact of a door-to-door strategy on COVID-19 immunizations at GK Prison and Gataka dispensaries from October 2022 to May 2023. Prior to the door-to-door strategy, vaccination numbers fluctuated particularly at Gataka, which saw a significant drop. After the implementation of the door-to-door strategy, vaccinations at GK Prison Dispensary steadily increased from 1372 in February to 1997 in April. At the Gataka Dispensary, the number of vaccinations also increased substantially, with a peak of 1112 vaccinations in March. There was a slight decline in May 2023 due to stock out of Pfizer vaccines in the county.

Community Mobilisation for Vaccinations

Community Health Volunteers (CHVs) are incorporated into vaccination teams to help mobilise community members at the household level and in high-traffic areas, given their trusted status within these communities. Ann highlights that including a CHV in the team often eases access to the community. She observes that communities are generally more accepting and receptive when they see one of their own participating in the process

Jackline Anunda, a Community Health Promoter serving Noonkopir Village for over five years, and a member of the COVID-19 vaccination team, identifies vaccine hesitancy as the greatest hurdle in her work. She encouters people who either deny the existence of COVID-19 or adamantly refuse vaccination. Jackine says, “ It requires clear communication to deconstruct the myths and misinformation to help people understand the importance of getting vaccinated”.

Jackline further adds that despite their efforts to sensitize the community through health talks during household visits, significant information gaps exist that hinder vaccinations. She says, “ the community often misinterprets messages from the Ministry of Health, thinking that because mask mandates have been relaxed, the disease is no longer a threat, and they question the need for vaccination.” Regardless of these challenges, Jackline remains steadfast, promising to continue until everyone in her community receives all jabs necessary to protect them from COVID-19. Continous mentorship is also provided to the community health promoters by the health worker to build their capacity.

COVID-19 Vaccination Integration with other Primary Healthcare Services

The door-to-door integrated approach offers routine childhood immunisation services, Vitamin A supplements and dewormers for children under five years and COVID-19 vaccinations for adults. Simon Mwangi , the Clinical Officer at Gataka Health Center believes that this approach effectively reaches parents and guardians who bring their children for deworming and Vitamin A supplementation. After sensitization, these adults often choose to get the COVID-19 vaccine. In conclusion, the door-to-door integrated approach has proven to be a successful strategy in improving COVID-19 vaccine coverage and bridging the gap in vaccines access and equity, suggesting its potential for replication in other settings.